Understanding Net Present Value (NPV)

Welcome! In today’s post, we’ll walk through the concept of Net Present Value (NPV) and how to calculate it accurately in Excel. If you’ve ever wondered how to measure whether an investment is worth it, NPV is one of the most practical tools you can use. But, as with many financial functions, there’s a catch. If you’re not careful, you might end up miscalculating by mishandling your initial investment. Don’t worry, we’ll tackle that together, and by the end of this article, you’ll know how to apply NPV in Excel the right way.

Video

Why Money Today is Worth More than Tomorrow

Before diving into Excel formulas, let’s ground ourselves in why present value even matters. Think of it this way: if someone offered you $1,000 today versus $1,000 spread over the next five years, you’d take the money today, right? That’s your financial instinct in action.

Money loses value over time due to factors like inflation, opportunity cost, and risk. So, dollars received in the future are worth less than dollars in your hand today. To account for this, we apply what’s called a discount rate, which is basically the rate you use to bring future cash flows back to their present value. Fortunately, we can compute this with precision using Excel.

Before we get to the NPV (Net Present Value) function, let’s get warmed-up with the PV (Present Value) function.

Exercise 1: Calculating Present Value with PV

Let’s use an example. With a discount rate of 10%, how much is a cash flow stream of $200 per year over five years worth today?

Excel makes this easy with the PV function. Here’s the quick breakdown of the function’s arguments:

=PV(rate, nper, pmt)- rate: the discount rate

- nper: the number of periods

- pmt: the payment per year

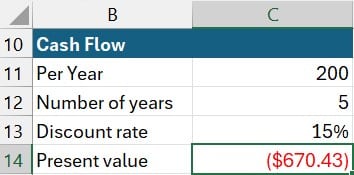

So, let’s apply this to our workbook and write the following formula into cell C14:

=PV(C13, C12, C11)The result shows a present value of about $758. That feels about right. Getting $200 each year over five years is worth less than $1,000 in cash today.

Note: by default, when the pmt argument is positive the function returns a negative number to represent positive inflows and negative outflows. You can easily flip the sign with a leading – if desired.

If you increase the discount rate to 15%, your present value drops to about $670.

This explains why, for example, lump-sum lottery payouts are so much lower than the advertised jackpot which is paid out over 30 years. Those future dollars just aren’t as valuable today.

Exercise 2: Present Value vs Net Present Value

Now that we understand the basics of the time value of money and the present value function (PV), let’s take our next step and talk about net present value with the NPV function. While PV assumes payments are the same each period, NPV lets you specify different cash flows each period.

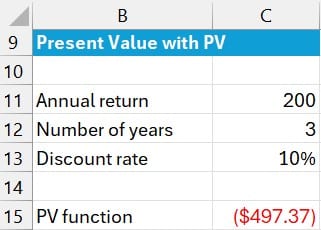

Let’s test them side by side. Suppose you receive $200 every year for the next three years with a 10% discount rate.

We could set our assumptions into some cells and then use the PV function like this in C15:

=PV(C13, C12, C11)

With identical payments, PV returns $497.

Instead of given Excel the amount per period and the number of periods, with NPV, we just give it the cash flow values per period, like this:

=NPV(C13, F11:F13)This also returns $497.

So why bother with NPV if PV returns the same amount? Well, NPV shines when cash flows aren’t the same. If year one is $200, year two is $300, and year three is $400, NPV can handle that variability easily:

But, what if all cash flows are not positive? Like, we have some negative cash flow years? Well, that takes us to our next exercise.

Exercise 3: Positive and Negative

If our future cash flows have a mix of positive and negative values, NPV can easily accommodate this situation. We just enter them into some cells, along with the discount rate, and then use NPV accordingly:

=NPV(C14, C8:C12)This returns $657.

But what if we wanted to consider the initial investment of say $500? We would just net the investment amount and the results of the NPV function.

We can use a formula like this:

=C15 + C16This gives a net present value of $157.

A word of caution: Don’t include the initial investment as the first cash flow inside the NPV function. This ends up discounting the initial investment as if it occurred in the future (time period one), which is incorrect assuming your investment is made at time period zero.

So, What Can We Conclude?

If your calculated net present value is positive, as in this example $157, that generally indicates the investment is worthwhile given your discount rate. Of course, in practice you might want to consider other factors, but from a cash-flow perspective, a positive NPV is a good signal.

Wrap-Up

Hopefully, this post cleared up how to work with NPV in Excel, and especially how to treat the initial investment properly.

If you have any questions or want to share your own NPV tips, please drop a comment below … we’d love to hear from you!

Sample File

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What’s the difference between PV and NPV in Excel?

PV is for identical cash flows (an annuity), while NPV handles varying cash flows over time.

Q2: Can I include the initial investment directly in the NPV function’s cash flows?

No. Excel’s NPV function assumes all cash flows happen at the end of each period, so you should subtract the initial investment after calculating NPV.

Q3: What does a positive NPV mean?

It typically means the investment is profitable given the discount rate you used.

Q4: What happens if cash flows arrive on irregular dates?

For that, Excel’s XNPV function is better because it handles cash flows with uneven timing.

Q5: How do I choose the right discount rate?

It depends on your opportunity cost, risk, and other financial assumptions. Often, people use their required rate of return.

Q6: Does PV assume cash flows come at the beginning or end of the period?

You can specify that using the type argument in PV.

Q7: Are taxes or inflation included in NPV?

Only if you build them into your cash flow forecasts or discount rate as Excel won’t do that for you automatically.

Q8: Why do lump-sum lottery payments differ from the jackpot amount?

Because the advertised jackpot is usually paid over time, and the present value of those future payments is much less.

Excel is not what it used to be.

You need the Excel Proficiency Roadmap now. Includes 6 steps for a successful journey, 3 things to avoid, and weekly Excel tips.

Want to learn Excel?

Our training programs start at $29 and will help you learn Excel quickly.